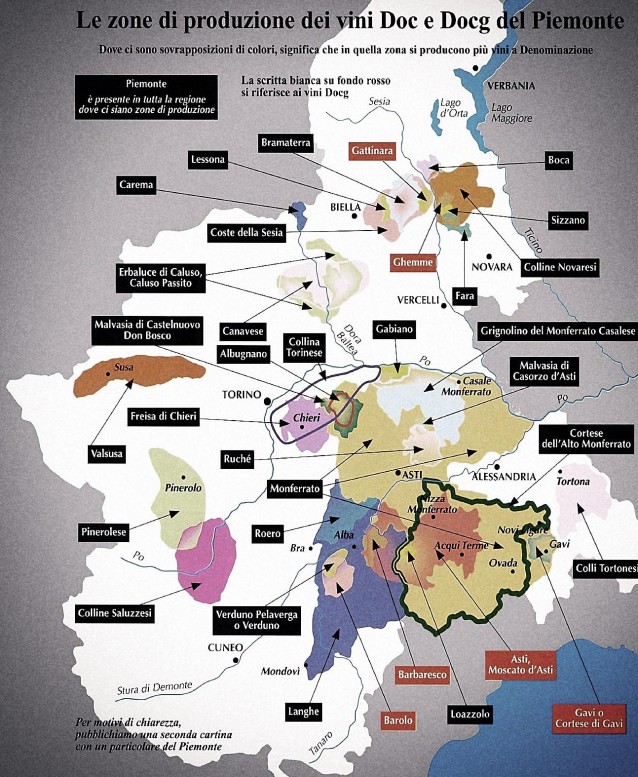

Surrounded on three sides by the Alps in the northwestern corner of Italy, Piedmont doesn’t feature a climate that readily conforms to the American, tomato-soaked stereotype of Italian food and drink. Rather, this is beef territory, where cardoons, garlic, and truffles are among the prized produce, and where the biggest, age-worthy reds of the area – Barolo and Barbaresco – have earned a large following around the world.

While those two famous expressions of southern Piedmont’s Nebbiolo grape are justifiably coveted, the area’s rich food and drink culture offers plentiful variety for the thirsty and curious. Last year, when we opened, we featured the Canavese Rosso from Luigi Ferrando, and as we head into this fall and winter, we’re leaning even more heavily on Piedmont across the menu.

2013 San Fereolo Valdiba

Dolcetto is a grape that seems poised for a resurgence with American wine drinkers. It’s affordable, easy to get, and when done well, a perfectly gulpable and food-friendly table wine. In the southern reaches of Piedmont, the area called Dogliani prides itself not on the prestigious Nebbiolo but on Dolcetto. That pride often manifests itself in the form of over-concentrated wines designed to compete for broader attention, but not so with the wines of San Fereolo. Winemaker Nicoletta Bocca makes a range of expressions of Dolcetto, and while her affordable entry-level wine is perfect to accompany a range of foods – like one might eat at a shared plate restaurant.

The farming and winemaking are everything we generally look for as clues to quality: biodynamic farming (albeit uncertified) of limestone-dominated vineyards, hand harvesting of grapes, relatively low yields, and fermentation with indigenous yeasts. The resulting wine is full of fresh mixed berry fruit balanced nicely with modest tannin and fresh acidity that are hallmarks of Valdiba, a notable sub-region of Dogliani. We fell in love with this last spring and brought it into Michigan for the first time to serve by the glass throughout the fall and into the winter.

2011 Aldo Conterno Langhe

Known for Barolo sourced from his vineyards near the famous town of Bussia, Aldo Conterno also makes an entry-level wine that we actually prefer and which we recently added to our reserve list.

Italian wine authorities give a lot of latitude to winemakers in this part of Piedmont via the Langhe DOC, a named region where the rules surrounding what grapes go into the wine are looser than most, leaving a great deal to the winemaker’s discretion.

In Conterno’s case, his Langhe Rosso is 80% Freisa and 10% each Cab and Merlot. Freisa has a long history in the region, arguably the most significant and prestigious grape in Piedmont prior to the post-WWII rush toward Nebbiolo. And indeed, Freisa is a genetic parent of Nebbiolo, so they share some characteristics. Surprisingly, Freisa can be even more tannic and acidic than its offspring, but that isn’t the case here, perhaps owing in part to the age of the wine. Rather, it features nuanced aromatics, darker fruits, and nice acid with just a bit of tannin on the finish.

2000 Conti Boca

Traveling north-by-northeast from Barolo, there’s a cluster of wine regions – Ghemme, Gattinara, Boca, and others – leading up toward the massive peak of Monte Rosa. Even the robust Nebbiolo here thins out and becomes lighter in color, lower in tannin, and higher in overall acid.

Boca, established as a DOC in the late 60s, requires that the wines must be 70-90% Nebbiolo and 10-30% Vespolino and Uva Rara, grapes that add a spiciness and color respectively. Wines are barrel aged for a minimum of 18 months, and a total aging time of 34 months. Riserva wines must be aged for 46 months, 24 months in barrel, and almost 4 years total.

Among the two dozen or so producers still working in Boca, Conti is the oldest. Begun in 1963, the winery has been passed to the three daughters of original winemaker Ermanno Conti. Their wines spend three years in barrel, and they have a very extensive library of older vintages. We were fortunate enough to be able to get a case of their 2000 vintage, which is drinking really well. Fresh and spicy with plenty of floral, cherry, and mineral notes, the herbal, moderately tannic finish makes this a bigger wine than one might assume at first glance.

2011 Ferrando Carema “White Label”

We’ve been serving the Boca mentioned above for a few months and are down to our last several bottles. As the wine gets drained off the reserve list, the replacement coming in behind it is a cult classic. North of Canavese and west of Boca, Luigi Ferrando makes some spectacular wines. While these were imported directly into Michigan back in the 70s and 80s, it’s been a long while since it’s been available regularly. Some of the better restaurants and wine shops in Michigan have periodically gotten their hands on some – notably, Trattoria Stella in Traverse City and Elie Wine Company in Birmingham – but sadly, it has otherwise been largely absent from the state. So we leapt at a chance to buy some this year.

In the hills leading up to Mont Blanc, Ferrando holds about 15-16% of all the vineyards in Carema where he grows Nebbiolo with full southern exposure. Here, acidity is not a problem – rather, it’s getting full sunshine and ripeness. So in addition to his choice vineyards, he trains the vines onto a pergola to maximize said sun exposure. The wines are eventually aged in barrel for about three years, give or take a few months, depending on the vintage and then aged in bottle for another year (Carema must be aged four years before release).

This is a very elegant, often floral and spicy expression of Nebbiolo with hints of cinnamon, mineral, smoke, and just enough tannin. The acidity is lively and fresh. We have access to a couple of bottles from the 60s and 70s, which we hear should still be youthful and nuanced, but we have yet to crack them open to see for ourselves. Despite the reported durability of these wines, we know from first-hand experience that this 2011 bottling is drinking quite well right now. We’ll look forward to adding this to the wine list after we sell out of the Conti Boca.

The following map, which we found floating around the internet without any attribution we could see, outlines a number of the regions discussed above:

The latest such bottle is from Swiss producer Cave Caloz from a region in the Alps, near the northernmost end of the Rhone river, called Valais. The wine is made from a charming, difficult-to-grow, unheralded grape called Cornalin (also known as Rouge de Pays) that is almost exclusively grown in Valais.

The latest such bottle is from Swiss producer Cave Caloz from a region in the Alps, near the northernmost end of the Rhone river, called Valais. The wine is made from a charming, difficult-to-grow, unheralded grape called Cornalin (also known as Rouge de Pays) that is almost exclusively grown in Valais.