Plenty of great wines – and beers; and sakes; and ciders – are available here in Michigan. But every now and then, we encounter something seldom seen here that is so outstanding we feel obligated to seek it out for the menu. Here are a few such recent additions:

Dassai Otterfest 23 Sake

Last summer, we added Dassai Otterfest 50 to our menu after a staff tasting that spawned an infatuation with sake. Our guests who enjoy the classic Japanese rice “wine” will know that the 50 in the name refers to seimaibuai – the percentage of a rice grain left after it’s been polished to prepare it for the brewing process. Previously unfamiliar with Dassai, we learned that they offer both a 39 and a 23, the latter being a figure that is truly astounding: Consider that 77% of a single grain of rice is essentially thrown away to get only that eminently fermentable center.

Sake lovers (and really, anyone who loves delicious things) will be excited to hear that the Dassai Otterfest 23 is now on our reserve list. Our pals at Great Lakes Wine & Spirits helped bring it in for us, and we couldn’t be happier: It’s an astonishingly delicate, elegant beverage. No, not beverage: Ambrosia. Nectar. Of the gods.

In terms of food, think of it as a superior rose and pair it with seafood or root vegetables. Or just drink it with a grin.

This sake is listed in many east coast retail shops for around $100. To encourage Detroit’s sake lovers and curious beverage aficionados to give this treasure a try, we’re selling it for just about the same price — $110/bottle.

2013 Ferrando Erbaluce di Caluso

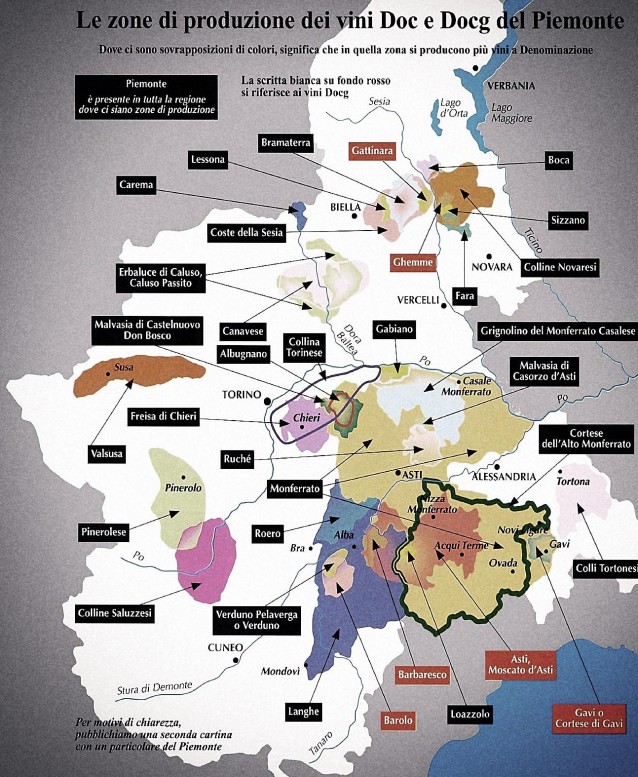

All too rare here in the Mitten, the wines of Luigi Ferrando are universally charming and delicious. This winter, we’re excited to be pouring their Erbaluce by the glass ($10). A white grape indigenous to the mountainous northwestern part of Piedmont, Erbaluce is known for producing high acid, mineral-driven, dry wines – a perfectly versatile white to accompany a wide-ranging restaurant menu.

The Ferrando family has been making wine in this part of Italy since about 1900. Their “white label” Carema – a miniscule appellation known exclusively for its elegant, high-elevation nebbiolo – has achieved genuine cult status in the United States. Further down the mountain is the appellation of Canavese where they make a delightful rosso that we poured by the glass when the restaurant first opened. Within Canavese is the town of Caluso, about 45 minutes north of Torino, which is where their Erbaluce is grown, eventually fermented and aged in stainless steel.

Ferrando’s expression has an unusually rich body, densely packed with luscious fruit and herbal notes before a long, refreshing finish. Complex enough to be intriguing to wine lovers and quaffable enough for anyone with access to a patio to enjoy, it’s rapidly become a house favorite. We brought enough in from New York to last us well into the spring.

2014 Thierry Germain Franc de Pied

Despite some recent good press, France’s Loire river valley is still an underappreciated source for wine. Our friends at Elie Wine Company in Birmingham turned us on to Thierry Germain, an up-and-coming producer whose winery, Domaine des Roches Neuves, is drawing some comparisons to the legendary Clos Rougeard. Indeed, they were recently awarded 3-stars by the Revue du Vin de France, an honor reserved for only those two estates in the Loire.

A transplant from Bordeaux, Germain has been making his wines since the early 90s, but in 2000 he converted everything to biodynamic farming and has refined his approach, keeping alcohol levels low and finding structure from using whole clusters of grapes.

Franc de Pied is French winemaking shorthand that references a vine’s own rootstock. Many wine lovers are familiar with phyloxera, the louse that decimated Europe’s grape vines in the 1800s. After the scourge, winemakers took to grafting their vines onto American rootstock which was resistant to infection. Germain’s Franc de Pied, true to its name, is thus ungrafted. Whether that adds extra depth or not is beyond our palates, but it’s hard to argue with the results: The wine is tremendous.

Like many of his reds, Franc de Pied could enjoy a brief sojourn to a decanter (or a few years in the cellar), but among his offerings, this is among the most generous, with a nose of flowers and raspberries, notes of black currant and herbs, good structure, and a surprisingly mineral-driven finish. Light in body but rich in color and flavor, this is truly a Burgundian cab franc.

Less than 80 cases of this wine are made in a given year. We’ve got a few of them stashed away, and they’re on offer for $65/bottle until they run out.